Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a weekly column dedicated to doing exactly what it says in the header: shining a light on the some of the best and most relevant fiction of the aforementioned form.

Neil Gaiman’s conception of Caitlin R. Kiernan as “the poet and bard of the wasted and lost” has featured on any number of Kiernan’s covers through the years, and though it was once a decent description of her position — and a quote which particularly appealed to me as a teen in a leather trench — it has seemed increasingly inaccurate in the decade and change since her debut.

For a start, her fiction is now far less angsty, far less for and of the wasted and lost than it was. Furthermore, Kiernan has done away with the flashiest aspects of her painstakingly composed prose. In 2013 her writing is as challenging as it’s ever been… but we want our authors to push out the boundaries and play with our expectations, do we not? To dare to dream of the weird and wonderful, as Kiernan has — and to considerable critical acclaim through the ages.

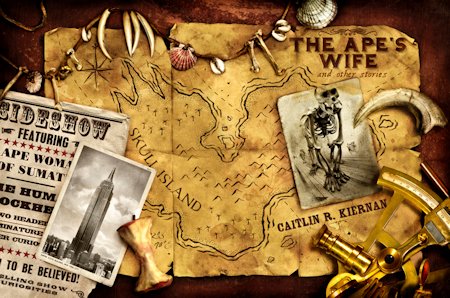

Despite this she has struggled to make much of an impact on the market, and The Ape’s Wife and Other Stories — her twelfth collection in twelve years, if you can credit it — is unlikely to change that unfortunate fact. Yet to those of us with a willingness to follow in the footsteps of her darkly fantastical fiction, it evidences an author at the very height of her dizzying abilities.

By design, the focus of The Ape’s Wife and Other Stories ranges far and wide:

When I sat down to compile this volume, looking back over my earlier and somewhat “themed” collections, I determined this would, instead, present a wide range of the fantastic, a collection that wanders about Colonial New England cemeteries, then sets off for Mars. That is content, one page, with werewolvery and ghosts, then a few pages later it’s busy with steam-driven cyborgs in the wild west, before careening into a feminist/queer retelling of Beowulf, just prior to landing amid the intrigues of a demonic brother in 1945 Manhattan that won’t be found in any history book.

Today in the Short Fiction Spotlight, in order to demonstrate the depth and diversity of this short but provocative volume, we’re going to take in a trio of its enticing tales. You could categorise the first of these, “The Steam Dancer (1896),” as sensual steampunk. Truth be told, though, it’s more of a portrait of a character called Missouri Banks who works as a dancer in the Nine Dragons, “a saloon and whorehouse […] on a muddy, unnamed thoroughfare.”

Crucially, however, Missouri is different from Madam Ling’s other employees:

Her clothes fall away in gentle, inevitable drifts, like the first snows of October. Steel toe to flesh-and-bone hell, the graceful arch of an iron calf and the clockwork motion of porcelain and nickel fingers across her sweaty belly and thighs. She spins and sways and dips, as lissom and sure of herself as anything that was ever only born of Nature.

Missouri is half steam-machine, we see, but at heart wholly human; a beautiful fusion of flesh and metal, not cowed but empowered by her otherness. “She is not a cripple in need of patron saints or a guttersnipe praying to black wolf gods, but Madam Ling’s specialty, the steam- and blood-powered gem of the Nine Dragons.” Rather than disturbing her, Missouri’s injuries have made her singular. Distinct. Perhaps even happy.

She certainly happy is when she’s dancing:

And there is such joy in the dance that she might almost offer prayers of thanks to her suicide father and the bloatfly maggots that took her leg and arm and eye. There is such joy in the dancing, it might almost match the delight and peace she’s found in the arms of the mechanic. There is such joy, and she thinks this is why some men and women turn to drink and laudanum, tinctures of morphine and Madam Ling’s black tar, because they cannot dance.

There’s not a whole lot to the plot of “The Steam Dancer (1896)” — Missouri’s mechanical leg plays up at one point, which leads to a minor crisis — but this doesn’t detract from the power of the sensitive sketch at the story’s core.

The unreliable narrator of our second short is as fascinating a character as Missouri, if not nearly as pleased with her anomalous lot in life. It’s 2077, and Merrick lives in captivity, in an asylum of sorts — though she is quick to stress that she is not neglected. She is “too precious a commodity not to coddle,” after all:

I’m the woman who was invited to the strangest, most terrible rendezvous in the history of space exploration. The one they dragged all the way to Mars after Pilgrimage abruptly, inexplicably, diverged from its mission parameters, when the crew went silent and the AI stopped responding. I’m the woman who stepped through an airlock hatch and into that alien Eden; I’m the one who spoke with a goddess. I’m the woman who was the goddess’ lover, when she was still human and had a name and a consciousness that could be comprehended.

Originally published in Eclipse Three, “Galápagos” is an impressive epistolary piece assembled from a week’s worth of the journals Merrick writes on her doctor’s orders. In classic Kiernan fashion, its nonlinear narrative unravels via a series of “switchbacks and digressions and meandering,” yet the reader is eventually able to piece together a picture of what happened to its psychologically shattered protagonist. Of “the myriad of forms that crawled and skittered and rolled through the ruins of Pilgrimage,” and of what Merrick’s lost lover Amery showed her there; the very visions which have haunted her since.

There are sights and experiences to which the blunt and finite tool of human language are not equal. I know this, though I’m no poet. But I want that caveat understood. This is not what happened aboard Pilgrimage; this is the sky seen through a window blurred by driving rain. It’s the best I can manage, and it’s the best you’ll ever get.

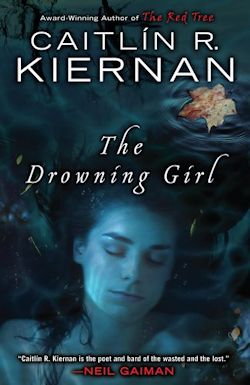

For its sensitive exploration of gender, “Galápagos” earned Kiernan pride of place on the Honour List of the 2009 James Tiptree, Jr. Award — which award The Drowning Girl subsequently won — but this desperately unsettling science fiction story should be required reading for anyone with an interest in the darker half of all that the genre offers.

Finally for today, we come to the tale from which the collection takes its title, and fittingly, “The Ape’s Wife” represents a kind of crystallisation of Kiernan’s disparate interests. It’s an All-At-Once account of pain and palaeontology and “possibility and penitence,” of monsters and madness, dreams and desires, alienation and love — and loss, obviously. It just so happens to be about a handful of the things that could have happened following the film King Kong:

The moments flash and glimmer as the dream breaks apart around her, and the barker rattles the iron bars of a stinking cage, and her empty stomach rumbles as she watches men and women bending over their places in a lunch room, and she sits on a bench in an alcove on the third floor of the American Museum of Natural History. Crossing the red stream, Ann Darrow haemorrhages time and possibility, all these second and hours and days vomited forth like a bellyful of tainted meals. […] Here is the morning they brought her down from the Empire State Building, and the morning she wakes up in her nest on Skull Mountain, and the night she watched Jack Driscoll devoured well within sight of the archaic gates. […] Every moment, all at once, each as real as every other; never mind the contradictions; each moment damned and equally inevitable, all following from a stolen apple and the man who paid the Greek a dollar to look the other way.

“The Ape’s Wife” is quite frankly enrapturing. It was far and away my favourite of the stories I read for the first time in this excellent collection, and that’s not nothing coming from someone who has — or perhaps had — little interest in the fiction it refashions. That Kiernan is capable of transforming the fodder of (let’s face it) fan-fiction into a story as sophisticated as this speaks, I think, to her inimitable ability to imbue feeling and meaning into whatever subject she sets her sights on, whatever the genre it falls from.

Over the years it’s become increasingly clear that one simply cannot classify Caitlin R. Kiernan, but damn it all, I’m going to try, because she is to my mind one of the century’s finest writers of fantastic fiction. That she continues to be so woefully overlooked recalls the resonant refrain of this collection’s titular tale, namely the portrayal of the world as a steamroller.

Well if anyone can stop its relentless, wrecking rampage, its hollow promise of progress, Caitlin R. Kiernan can.

The Ape’s Wife and Other Stories is available November 30th from Subterranean Press.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He’s been known to tweet, twoo.